Between the years 2005 and 2010, the nature of the modern world shifted. The transformations are now known, but they appeared in few headlines at the time. Nor did they attract commentators and others who often hope to seize and climb upon events in the hope of seeing further. Three of the changes can be stated simply:

1. For the first time in history, and probably the last, most homo sapiens were living in cities.

2. The center of global energy use passed from Western nations to the developing nations, especially in Asia.

3. Humanity faces an unexpected, spectacular abundance in fossil resources, esp. oil and gas.

An Urban Future

I will start by saying that every adult—particularly if they are parents or plan to be—needs to know that humanity’s future is the city. If you don’t like cities, that’s fine for now. But it would be an error to raise your progeny thinking that urban existence is bad or evil. Predictions say that by 2050 (only 24 years away), 65%-70% of us (see graph) will live in metropolitan areas of 100K up to 37+M (yes, million, as in Tokyo today).

Fear not: Earth will not be paved from pole to melting pole, like the planet Trantor in Isaac Azimov’s classic Foundation series. I’ve calculated that only about 3% of the land surface might be covered. That’s a fair bit, though. It includes thousands of square miles of solar and wind farms.

Cities are the forges of the world. They are fueled by electricity and oil (transport) to create work, knowledge, and economic output. One of the most hopeful advances today, in fact, is electrifying vehicles. Transport, concentrated in metropolitan areas, is the largest source of climate-changing emissions in wealthy countries. What also matters, then, is how many and which vehicles we electrify, plus what sources we use to generate the added electricity, topics for a later post.

China Syndrome

The first two points above are related. They are linked through another fundamental change—China’s replacement of the U.S. as the world’s largest energy consumer and producer of carbon emissions. China, that is, in about 2010, had suddenly become hugely essential to any Energy Transition, thus the globe’s ability (or inability) to deal with global warming. If you weren’t talking about China from then on, you weren’t talking about the energy or climate future.

This truth was soon undeniable. China’s crash program of massive economic development and mass urbanization and its immense reliance on coal and oil—coal, because the country has very large resources of it; oil, because there were no alternatives for modernizing transportation—led to its spectacular rise in emissions. These rapidly came to exceed North America and the EU combined (before Brexit).

That the Chinese government also accepted the truth of climate change (as well as the truth that 5 is larger than 3) and began to develop non-carbon sources of energy—hydropower, solar, wind, and nuclear—made more than a few cheer the country as heroically leading a “green revolution.” We have since learned better. China’s leaders have no intention of eliminating their nation’s dependence on coal, which is greater than all other countries combined (more about this, too, in a later post). There is also the small question of whether we want an autocratic police state that crushes dissent, imprisons journalists, and erects concentration camps to serve as the world’s leader toward greener pastures.

For over 200 years, since coal and steam first launched modern industry and mobility, the West was the pounding heart of modern energy. That long era, with all its mixed blessings, has ended. Consequences are already epochal. But it may be too early to designate heroes and villains.

More than Imagined - Why Now?

My last point will be a shock to some readers. But it does not divert from fact. It does suggest, however, that while history may or may not repeat itself, it does have a distinct sense of irony. At the very moment when the world must shift away from fossil fuels, it has discovered a vast and potentially accessible “treasure” of them.

How can this be? Merely a decade ago debate raged over impending scarcity, embodied in the concept of Peak Oil. This predicted a near-term limit in production, after which oil flows would go into precipitous decline, bringing economic hardship, collapse, war, and, yes, “the end of civilization as we know it.” It was a hypothesis that fit well the belief (inherited from 18th century thinker, Thomas Malthus) that humanity had reached the Earth’s carrying capacity and was headed for the cliff, eyes wide shut.

So why is scarcity is not at the door? The short answer is: technology. Fracking is part of this, but only a part (I will have a post on this too). In combination with other advances, it has revealed that the most common rock type near the Earth’s surface—shale—often contains more oil/gas than previously thought, and that these hydrocarbons can be potentially mobilized. The technologies were first used in U.S. gas-bearing shales, whose production rose so fast it flooded the market, causing a price collapse. Companies then shifted to oil-rich shales. This proved no less successful and eventually had a similar effect, this time on global oil prices. Suddenly, it was evident that there was far more potentially producible oil/gas than anyone previously believed. This didn’t mean shales everywhere were a guaranteed; geologic history has made them extremely diverse in properties and resource potential. Yet this merely moderates the immensity of the new global possibilities.

These, after all, include other dimensions. The same technologies make possible redevelopment of many older, even abandoned, oil/gas fields in non-shale rocks. Many such fields, using existing methods, only recovered around 20%-25% of the original resource in-place. Once you understand that there are literally thousands of such fields worldwide and that the new technology could possibly double recovery, you understand why enormous new volumes now seem within reach. You can also comprehend why some people are strong on getting carbon capture and storage to work commercially (it’s still too expensive in most places).

Today, “fracking” is a political term more than anything else. Whether you hate and fear it or are more neutral, you deserve to know what it really involves, and (as an ex-industry insider) I will provide this in the near future. But however you feel about them, frac technologies aren’t the primary reason to reduce fossil energy use. I live on the West Coast of the U.S., where, aided by a warming climate, wildfires are now an annual, growing threat to millions of us.

Minerva’s Owl and Bitter Hindsight

A brief story. In 2003, the Bush Administration invaded Iraq on a false claim (fancy talk for “lie”), with several goals: creating a democratic ally in the heart of the Persian Gulf, an ally that would help constrain Iran, incline other Gulf states toward democracy (and U.S. influence), and keep oil flowing to the global market. The last goal was critical. America was then the world’s largest crude importer. With the Soviet Union gone, “foreign oil” was considered America’s #1 national security threat.

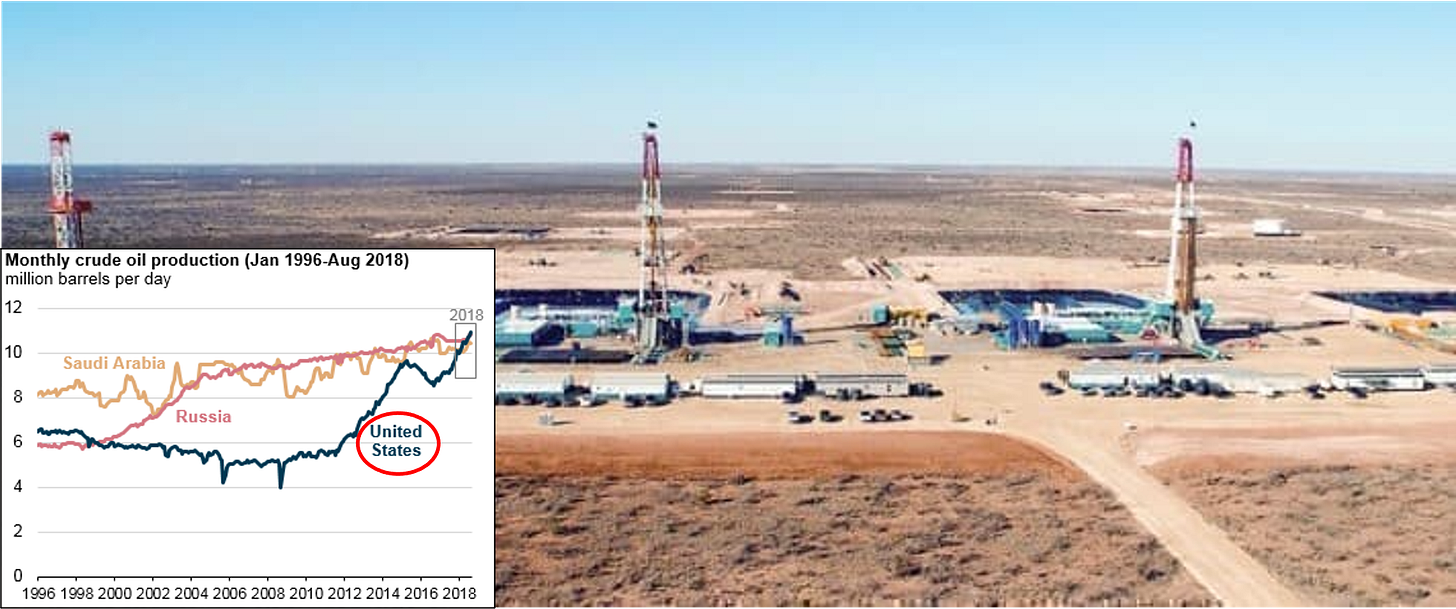

But then, as if by magic, the situation flipped. U.S. crude production soared; imports fell. In less than a decade, America had become the world’s largest oil producer and a new exporter (see graph). Experts were stunned. So was OPEC. American oil now competed with that from Gulf States. The geopolitical landscape had been utterly transformed.

Reality, aided by the “fracing revolution,” had outdone prediction. OPEC and Russia, petro-opponents for many decades, joined forces to try and forge a new cartel in the face of shale production. Conservatives were ecstatic; U.S. “energy independence” was nigh; national security was elevated. President Trump spoke of American “energy dominance.”

And the Iraq invasion? Foolish and unnecessary from the energy viewpoint. As for the other goals, given the horrific chaos, death, and terrorism that resulted, the decision to invade turned its own objectives inside out, transforming them into vicious threats. All told, the worst foreign policy move the U.S. has ever made.

With a wry glance, Minerva’s owl glides through the twilight, reminding us that wisdom too often arrives after its necessity has past. But in this case perhaps something can be rescued for the future. There is more than one reason to lessen the need for liquid petroleum.