Apologies for taking some time to get this out. I had carpal tunnel surgery, which somewhat reduced my typing capabilities (among other minor things, like eating, lifting anything heavier than an earbud). But posts will now appear more regularly, at least until the other hand is done. Such are the wages of age.

Continuing, then, our discussion of global change, there are three other transformations to the energy fabric of the world that I’d like to talk about. As in Part 1, I’m concentrating on a remarkably brief time period, in this case between 2000 and 2010. Of course, if we look further back, to 1980 for example, there are other changes to be seen in other areas of human life-- advances in child health, education of girls, decline in abject poverty, and more—which have been treated with panache by the late Hans Rosling, who made statistics cerebrally sexy and visually stunning (see one of his TED talks and the brain-expanding Gapminder site he founded).

I choose the first decade of the 21st century, however, for a simple reason. Overall energy trends worldwide did not much change for a half-century, in some ways even longer, until the early 2000s. Oil, natural gas, and coal ran the world, and, with the added source of nuclear power from the 1960s, they seemed destined to dominate for many a decade into the hazy mists of the future.

But in the first ten years after 2000, there appeared a series of new and unexpected developments. Part 1 outlined three of these—the majority of humanity now living in cities; a west to east shift in the center of global energy; and technology revealing an immense abundance in oil & gas, exactly at the wrong historical moment.

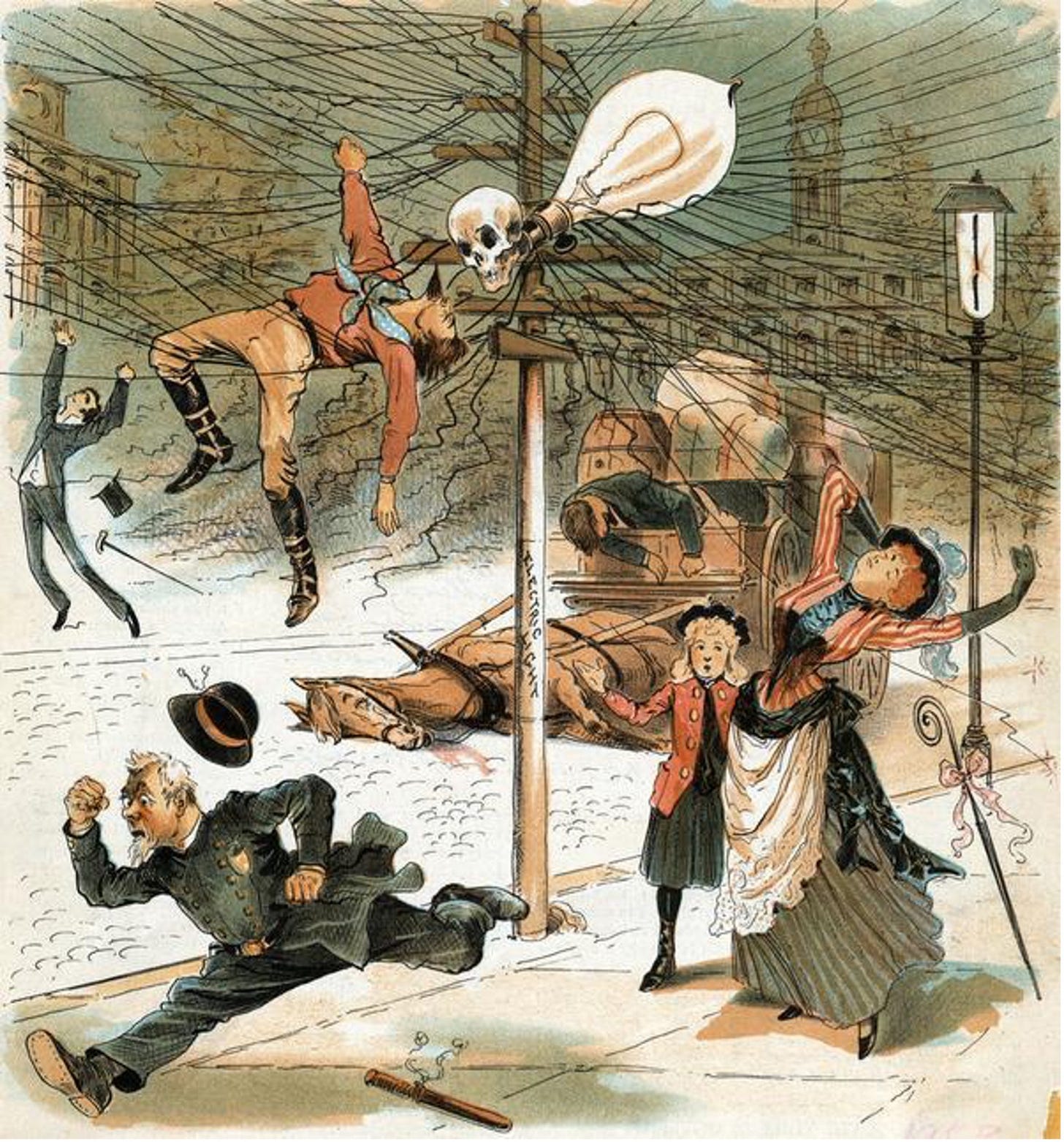

Again, these are global trends. The word “trend” is essential. It cautions against the idea that the exact same phenomena are in evidence everywhere, and that deep, lasting transformation can be completed quickly and in full. Energy transitions take time and do not arrive without potent resistance and massive casualties. This is because they represent, in concrete ways, the building of a new reality. They involve new political, economic, and cultural dimensions to life, including new psychologies. They are the inevitable source for a new organization of society itself—consider how the shift in western nations from coal to oil (between roughly 1910 and 1960) altered transportation. Or how electricity has modified every aspect of life over the past 120 years and will continue to do so (subject of a future post). This, too, was resisted and debated early on.

Periods of major energy change alter the journey of human existence. Here are three more proofs of this:

1. Human society has entered an era of rapidly ageing. By 2050, nearly 20% of the world will be 65 or older, with sub-Saharan Africa the only probable exception.

2. The history of modern energy from 1800 to 2100, now appears to have revealed itself. It will consist of three major periods. We have just entered the second of these.

3. At the same time, a true Energy Transition is now solidly underway and will be as irreversible as those in the past. Its results will take longer and be more complex than commonly realized.

Clock of Ages

It happens. People get older. Their bodies grow weaker though their minds can stay strong (if they’ve used them previously), which means their lives contract in certain ways, expand in others. All this is gaining attention, since global ageing is now in acceleration mode.

A recent report on this by the Population Division of the UN says: “Population ageing is a human success story, a reason to celebrate the triumph of public health, medical advancements, and economic and social development over diseases, injuries and early deaths that have limited human life spans throughout history.” In short, global ageing is a mirror image of global longevity—many more people living long enough to be “elderly.” In numerical terms for the US, one out of every four 65-year-olds today will live into their 90s.

If you happen to be 65, this is breathtaking. In my own youth, reaching the age 65-70 equated to an arrival at the Gates of Hades. Today, comparatively healthy people aren’t considered “elderly” until at least a decade beyond this. A glance at selected data for life expectancy (see graph) reveals most of this has come about since 1980. All of the countries and regions shown had surpassed a 65-yr life expectancy by 2010. Yes, richer people in richer countries tend to live longer, but this is an old truth. On the other hand, look at South Korea—an incredible story of gaining nearly 20 years in longevity since the early 80s, about 1 year of extended life for every two years lived (imagine if this could be continued; you’d get another half-century after 65). Indeed, the data also shows that less-rich countries are now only about a decade or so “behind” richer places, whereas in 1980 they were 2-3 decades away.

It is a point that Dr. Rosling often made with emphasis: people on average have become progressively healthier nearly everywhere. For quite a while now, it’s been the bad guys in movies who smoke, not the cool ones (some exceptions—Billy Bob Thornton in Goliath). To be clear, it’s a process. But people in poorer nations now live as long as Americans in the 1970s.

Older people consume energy differently than those 45 and younger. This means, in a majority of cases, 20%-30% less overall, on an annual basis. In a general sense, energy use per capita for people 65 and up rises or falls as a function of income. This is obvious for rich couples in their 70s—with big houses (often >1), pools, boats, several cars, walk-in refrigerators, etc. The 1%, however, are much less important than the 99%.

When people of more common means reach their late 60s and 70s, they tend to spend more time at home, live a somewhat quieter existence, and use more electricity (but not a large amount more). They also drive less, eat less, buy fewer clothes, need less “stuff.” They don’t have infants and young children to look after, and they often try to spend less. More than a few seek to downsize, even moving into smaller quarters. In lower-income countries, older people generally live with their families, and this is still true for the new middle classes in places like India, China, Latin America, and Africa.

The one area where energy use goes up significantly, of course, is healthcare, which mostly means electricity. This can vary a huge amount, from frequent or lengthy hospital visits for diagnosis and therapy, to at home treatment (e.g. dialysis, daily nurse care), to just a few yearly visits and a smaller number of procedures. Overall, though, hospital care—including emergency room visits—tend to rise with age

Hospitals are large users of power, heating, cooling, and hot water. They make-up about 2% of commercial buildings in the U.S. but consume nearly 9% of the sector’s energy. This amount has been dropping, though. Many efforts have gone into reducing costs (recall: health in our wonderful system is a commodity for profit) via more efficient medical equipment, heating/cooling (HVAC) systems, LED lighting, use of thermostats in patient rooms, and more. This will almost surely continue. Indeed, electricity use overall will likely gain in efficiency as systems are more fully digitalized and streamlined. True, if Japan be an indicator, we may have many robots running around, taking care of more than a few needs. But these will likely be nourished by battery technologies and won’t hugely deepen power demands.

So ageing societies look like they will use less energy overall. Though the angels and demons will be in the details, younger people in general are more active social and economic participants. This will remain true even as societies make adjustments (and they already doing so) to the reality of having a lot of older adults around. A core point to take away from all this is that an ever-growing number of societies will be peaking in their energy demand and consumption. This has already happened in a number of advanced, wealthy nations (a future post will take this up, too). Such is good news, in a sense, esp. when we view it in terms of emissions and what looks to be the long-term history of energy use in this century.

Global Energy History – Past and Future

One of the big changes in Part 1 was that by 2008-2010, energy consumption by wealthy, westernized nations had stopped growing. Thus ended the first and longest era of modern energy use between 1800 and 2100. The second era has now begun.

In this new era, Asia has become the controlling center of global demand and consumption. When an oil tanker departs the Persian Gulf today, for example—let’s say a very large crude carrier, or VLCC, carrying about 2 million barrels (84 million gallons, or 318 million litres), it makes a left turn towards India, China, Thailand, or Vietnam. Only 15 years ago, it would have turned right, toward Europe and the U.S. This new era will likely last about 60-70 years, ending in the later part of this century sometime around 2080 or so. By that time, India and China will both have mature, post-industrial economies, run overwhelmingly by electricity, and level or declining populations.

The third era will then begin. This will see Africa become the center of global energy need and the source of greatest population increase, approaching Asia’s declining numbers. Africa will then retain this role to the end of the century and beyond. Such is how the energy future sketches itself out, in terms of economic progress, technological advance, population, and other factors.

What could happen to change these overriding trends? A lot. Let us count the ways: wars, pandemics, technological breakthroughs, colonization of the Moon and Mars (due to a Musk-Bezos-Gates partnership). Am I forgetting something? Oh, yes—the massive destruction of cities and coastal areas by sea level rise, rural areas devastated by wildfires and extreme weather, loss of agricultural land to drought and flooding, crises wrought by intense and long-lasting heat waves, all while a string of US presidents (in one of the parties) either deny anything is happening or blame it on immigrants and China.

But even so, the three fundamental eras of energy use seem very likely to happen. In broad terms, the world has evolved—and western observers have, to some degree, caught up to the reality—into three main groups of nations, which roughly correspond to the eras I’ve been discussing. These are: 1) the wealthy and technologically advanced countries (you know who they are); 2) nations with rapidly modernizing societies and developing economies (China, India, Brazil, Turkey, Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, etc.); and 3) the less developed, poorer nations that have yet to enter their main phase of advancement (many nations in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Middle East, Central America, etc.). Economists and some international institutions like the World Bank divide the third category into two on pure economic grounds (lower-middle-income and low-income). Yet in terms of energy use, it makes more sense to put these together.

Going forward, Group 1 will continue to set the pace for energy progress and technological advancement, though not entirely. Group 2 will have a hand in this, too, and will also be more important in helping transfer such progress to the third group. But Group 1 will remain for some time the crucible of new knowledge and technology, with some important exceptions. A crucial point, however, is that countries will long be variable in the details of their energy production and use—where Norway can derive the great majority of its electricity from hydropower, Turkey can get a fraction this way, and Saudi Arabia barely any at all. There will be much more to say about this in future posts. For now, the subject leads directly into the third big change at issue here.

The Energy Transition – It’s Real

Yes, it’s quite real. And it’s getting more so every year. It’s a massive and evolving transformation, which it has to be, and far more multileveled and complex than often believed (consider, again, what the introduction of electricity brought). Contrary to common assumptions, the Energy Transition is not about replacing fossil fuels with wind and solar. Some of this is happening, to be sure, but it constitutes only part of a larger series of modifications to the global energy system.

Climate change is a primary driver of the transition but not the only one. As the previous section indicates, the history of modern energy has shifted: a great deal of the future lies in the hands of the Global South, the emerging and rapidly advancing economies of the world. Motives here do not wholly overlap with those of wealthy nations and do not embrace a renewables-only scheme, esp. if it rejects hydropower. Many of them are more focused on energy security and modernization, economic growth, and public health. True, climate change is very much a “threat multiplier,” so affects these areas too. But so is the lack of a reliable or inclusive grid.

I can’t cover all of this here, though. I ask that you be satisfied for now (please) with a list including some of the major trends that make up this transition:

1. A key element has been the rise of energy as a topic of enormous and lasting concern in society. In the past, such levels of concern tended to be tied to oil prices. Now, there are manifold reasons that will keep energy issues in high importance.

2. China’s role in helping launch and advance the transition is crucial. It’s immense rush to industrialize since the late 1990s, based overwhelmingly on coal, proved the need for global change by creating spectacular levels of pollution, disease, and carbon emissions.

3. Each nation is now engaged in a struggle to lower its emissions while advancing a reliable and affordable supply of energy. Governments will continue to evolve in trying to balance these demands. They will not always be transparent about their reliance on fossil sources.

4. The geopolitics of the energy transition is also evolving. It is far from simple and involves new areas of competition and conflict. Here are three main dimensions to it.

a. Oil/gas exporting nations are resisting a decrease in these sources of revenue. Their leaders understand the push for decarbonization but view oil/gas as essential to the world. They have yet to diversify their economies and may suffer major effects.

b. Global non-carbon energy markets, esp. wind/solar and nuclear, are largely controlled by U.S. rivals China (solar and nuclear) and Russia (nuclear), plus a few U.S. allies like Denmark and Germany (wind) and S. Korea (nuclear). China’s Belt & Road program is having large impacts on electricity development in many Asian and African nations.

c. New technologies, such as wind turbines and electric vehicles (and batteries) highlight raw materials like lithium, cobalt, and rare earth metals. Restricted in occurrence, these are creating conflicts between have and have-not nations.

5. Decarbonization is a main goal. Pursuing it more aggressively, as is needed, faces hurdles in the form of perceived political, economic, and security issues. Non-exporting nations with fossil fuel resources see them as adding to energy self-reliance, employment, wealth. The transition is also about conquering such inertia, which will mean new ways of thinking.

6. Climate change is driving large growth in wind and solar power, a major advance. Yet the limits of these sources are too often ignored in the hope they offer a simple, near-complete solution. This draws attention away from other existing non-carbon options, esp. nuclear. Energy myths are themselves a hurdle to progress but will likely continue in some areas.

7. The energy transition is thus a battle over ideas, too. Different versions of the energy future are also different visions of society. Absolutist ideas (renewables only, a “cleaner” future) contrast with “all of the above” concepts (no revolution needed) and also hybrid visions (nuclear + hydro + renewables; a mix of centralized & distributed generation). Fighting over the future of energy will be itself a long-term reality of the transition.

These points are not at all comprehensive, but they do suggest how multidimensional the greater effort is and will be. People have compared the energy transition to making a U-turn in a massive oil tanker (VLCC), with all the time, space, and patience that are needed. But this is far too easy and straightforward. Consider, instead, redirecting the ocean currents themselves, from shallow to deep, and all the changes to life that this would bring.

One last thing. The Energy Transition is real, inevitable, and inexorable. It will not fail, unless the world fails. Its greatest foes are not fossil fuels, but people, esp. those with bad ideas that would reject it or overly limit its options and possibilities.