New Gospel?

Here is something that needs comment. A brief one will do, I think, because of its importance. Being truly concise is not always, or ever, easy. Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “I would have written a much shorter letter, but I didn’t have the time.”

This “short letter” concerns a new report: Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, from the International Energy Agency (IEA). Released in May, with colorful graphics and a dark message, it’s become a touchstone for climate talk in media of all kinds (example), and will likely remain so. Unfortunately, most who take it up as a revelation get it dead wrong.

To be fair, the IEA encouraged some of this by a misleading, if strategic, title. It is not a roadmap. In fact, it’s not a map at all, or any other kind of guide to the Himalayan terrane of the next several decades of energy change and unchange.

Fatih Birol, the IEA’s director, deserves our respect. He has a difficult job—that of a global umpire, who must make all sides love and hate him in equal measure. This is like trying to earn honor in the eyes of Vladimir Putin, Jeff Bezos, and Leonardo DiCaprio at the same time. Over the past decade, the IEA has been repeatedly attacked for both underestimating the capabilities of renewables and failing to promote a future in line with the Paris Climate Accord, i.e. net zero emissions by 2050.

Birol has received letters from researchers demanding, in less than dulcet tones, he re-navigate the IEA’s annual flagship report, World Energy Outlook (WEO). Given its global use, this must be altered, said the complainers, to show how the world can keep warming below 1.5 deg. C..

The IEA was born in 1974, a child of the OECD and the first oil crisis (1973-74). Its raison d’être is providing reliable info and policy coordination that alert these governments to coming supply problems. While its role has mutated over time, data and analysis on energy reality have remained the heart of its work, with other topics like politics closer to the liver or kidneys. The first WEO appeared in 1977; it went annual in 1998 and began to include projections of future energy demand and use, rooted in existing trends.

The letters to Birol wanted the WEO to be a different, more activist document. This would not only be a mistake but a loss to everyone, and Birol knows it. Instead, he had Net Zero by 2050 produced as a separate document, and this may have settled the matter (or not). Meantime, it has immediately become a kind of gospel in a godless world searching for tablets.

What It Says

Birol himself provides a somber and chastising forward to Net Zero. It begins:

We are approaching a decisive moment for international efforts to tackle the climate crisis – a great challenge of our times. The number of countries that have pledged to reach net‐zero emissions by mid‐century or soon after continues to grow, but so do global greenhouse gas emissions. This gap between rhetoric and action needs to close if we are to have a fighting chance of reaching net zero by 2050….

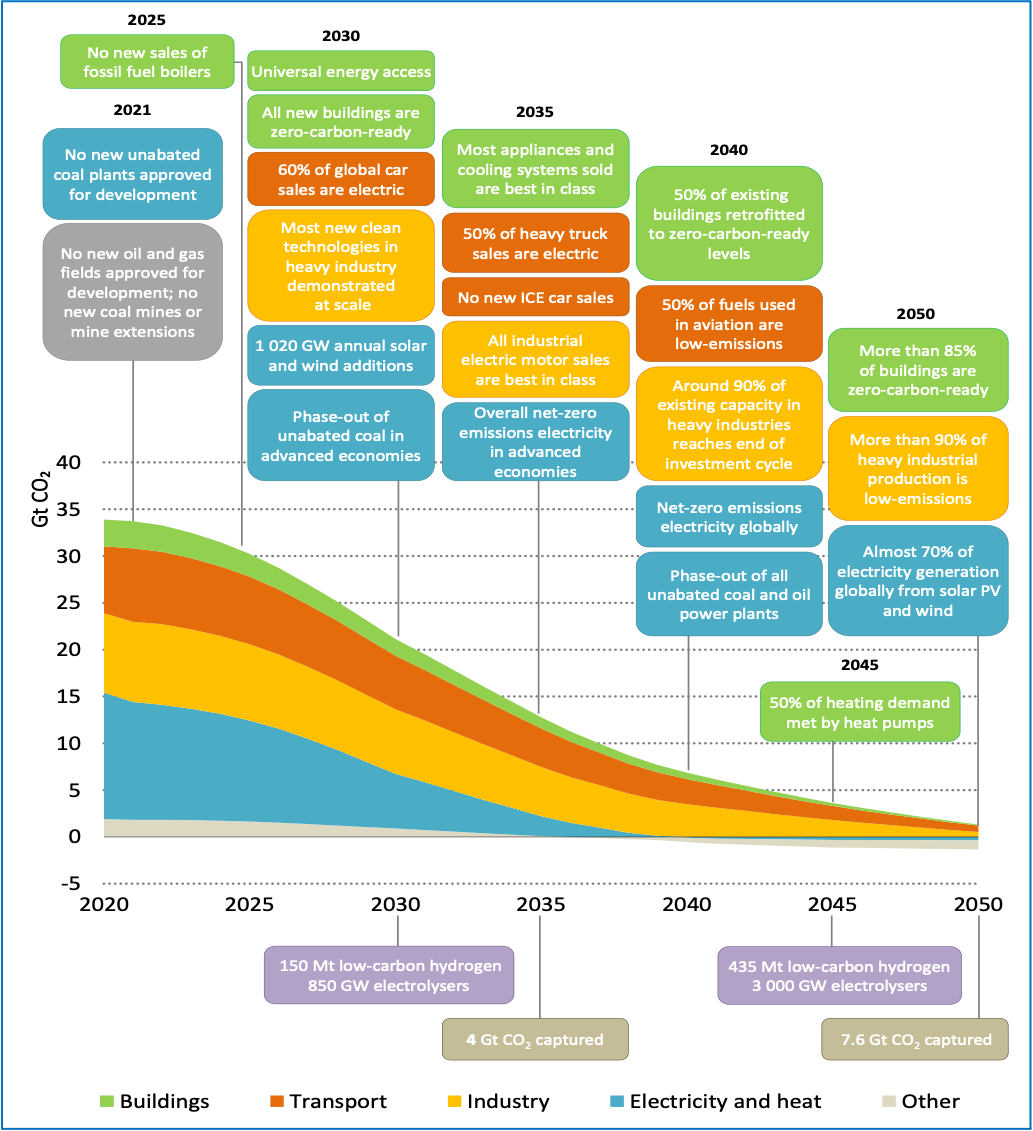

This report sets out clear milestones – more than 400 in total, spanning all sectors and technologies – for what needs to happen, and when, to transform the global economy… Our pathway requires vast amounts of investment, innovation, skillful policy design and implementation, technology deployment, infrastructure building, international co‐operation and efforts across many other areas.

The report required dozens of authors to write it and over 50 peers to review it. The International Monetary Fund gave help on macroeconomic analysis, while the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, a high-level data organization, aided computer modeling. This to say, the IEA did its homework and classwork.

There seems no problem with the data or the analysis. These are among the most sophisticated we now have about what it would take the world to achieve the report’s title. (Another recent effort of high quality, focused on the U.S. is Princeton’s Net Zero America project). Birol’s first paragraph, too, is sharply accurate—the “gap between rhetoric and action” is vast and real—and a key point that must be kept in mind.

I would draw your attention to that single number in the second paragraph. The figure below, taken from the report, shows some of the core milestones among The 400 (apologies to Leonidas and his Spartans).

The figure rewards both study and reflection. For those with large interest but little time, and who therefore prefer a “short letter,” I highlight only 3 of the telltale milestones:

2021 – No new oil and gas fields approved for development

2030 – Universal energy access

2035 – No new internal combustion car sales;

No New Oil/Gas Fields from 2021

In June of this year, there was a second major Black Sea gas discovery by the Turkish state-owned company, Tpao. President Erdogan proudly spoke of a “new era” for Turkey, which imports over 95% of its gas. Production from the new fields is to open by 2023 and will increase the country’s energy self-reliance. Turkey’s gas ambitions also extend to the eastern Mediterranean, where they have heightened historical conflicts with Greece over Cyprus and offshore territorial claims. Mr. Erdogan has sent warships to kindly accompany seismic survey vessels, a warning quite in line with his aspirations for regional power and influence.

Elsewhere, around 80 high-impact exploratory wells are planned for 2021, with the potential for major discoveries or for confirming earlier ones and therefore establishing new fields for development. These are being drilled in offshore Mexico, Brazil, Suriname-Guyana, North Sea, Barents Sea, Namibia, and northeastern Australia. More than 70% will be targeting oil prospects.

Back home states-side, headline news is full of worries about rising oil and gasoline prices--“highest in six years” is the phrase. The reason? Global demand is rising faster than supply. Per IEA’s own Oil Market Report for June (2021): “Global oil demand is set to return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022, rising 5.4 mb/d in 2021 and a further 3.1 mb/d next year…”

Universal Energy Access by 2030

This is UN Sustainable Development Goal 7. It stipulates energy must be “affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern.” Translation: no more use of traditional biomass (firewood, animal waste); dramatic cuts to fossil fuel use, huge increases in renewables, major electrification of every sector (transport, commerce, buildings, industry).

An electricity focus makes sense: since 2010, more than 800 million people have gained this essential form of modern energy for improving opportunity, health and healthcare, education, quality of life. Yet, two large questions hover: 1) How evenly shared has progress been? 2) What does “access” really mean?

First answer: “not very.” Power has newly gone to people in Latin America, SE Asia, and South Asia. But Pakistan, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Guyana, Nepal, Haiti remain behind. The big challenge is sub-Saharan Africa. Here, access is commonly under 50%, often below 30%. Between 575 – 750 million people still have none, and due to rapid population growth, the number is growing.

The UN Sustainable Development program insists that “Everyone in the world could have clean, affordable energy within the next 9 years if countries modestly “increase [annual] investments [to] $35 billion.”

No, they can’t. Not even at twice the price. Or three times. Consider just one country: Burkino Faso: population 20M; access to electricity 18%; gripped by violent crisis from jihadist attacks on villages, schools, and towns, massive displacement of people, hunger and illness, abuse by ethnic militias and security forces. Such is occurring across the Sahel, in Mali, Niger, Central African Republic, northern Nigeria. It is a humanitarian catastrophe for many tens of millions.

There is no building a grid or installing microgrids under these circumstances. And the idea of solarizing the entire Sahel? Two men with AKs could destroy a solar panel facility in a matter of minutes.

But it is not just conflict zones or other places of unnatural and natural disaster. Another deep difficulty with “universal access” is reliability. Dependable power for a modern energy system means having it 24/7/365, minus a few hours here and there (perfection is the enemy of realism). Much of the world, however, has access without this.

Researchers with Energy for Growth used a reliability limit of 12 hours per capita per year (the U.S. is around 5 hours). They found in 2020 that over 3.5 billion people lack dependable power (technical article here, paywall). That’s 45% of humanity, a figure likely to change one’s view about the state of the world.

Blackouts make for headlines and headaches in America, events not supposed to happen. But they are ordinary in Baghdad, Beirut, Dhakka, Kabul, Kampala, Dar Es Salam, Lahore, Delhi, Bangalore, Caracas, Sao Paulo, Manila, you get the picture. Reasons: grid systems poorly or incompletely built, not well maintained well, need investment for surging demand, too highly subsidized so no money for improvement (example: India).

Access is the first step in a voyage to reliability. Though there is no launch without it, each future step requires a journey of its own.

As for the last milestone given above—no internal combustion cars after 2035, I will ask only (as this “short letter” is growing long) who will corral and command all the world’s automakers to agree on this?

Not a Nice Thing to Say

There are multiple ways to deny reality in an existential crisis, like climate change. Early on, this was the refusal that global warming was fact. Such a position is no longer tenable. Most Americans now realize it is the equivalent to cultivating one’s garden as the lava approaches.

In the 2020s, there is another form of denial, grown stronger as the first has weakened. It says the world can transform and universalize its energy systems in one generation. Such is IEA’s Net Zero taken as a trail map—rather than a metric of how impossible, in real world terms, the stated goal is—how far the world remains from seriously dealing with emissions. Such is why we need the WEO as is, a more truthful view.

I do not enjoy saying this, but I find less pleasure in the necessity to say it. The situation is made worse, moreover, since so many who believe in net zero 2050 refuse to accept the most reliable and stable source of large-scale, non-carbon electricity: nuclear.

Energy experts who understand where things stand have already assigned the 1.5 deg. C goal to once-upon-a-time tale. Many feel they need to nod in public, avoiding the role of a slayer of angels, but shake their heads in private. A well-informed colleague commented to me during the recent Seattle heat wave: “We’re well beyond 1.5 and past 2.0; I want to know if we’ll get where we need to be before 3 degrees or even 4.”

I told him I didn’t know. I also do not know how damaging the denial of global reality will prove going forward, how much conflict it might create among those on the same side, how much it might misdirect ideas and decisions. Another strong belief—that so many smart, educated, and well-intentioned people can’t possibly be wrong—does not have a good historical record. How many thought WWI, the Great War, would prove only a brief and song-filled affair?