This past week saw a revealing series of energy events across the country that shocked a good many people, and for good reason. Today seems like a good time to share some salient observations. Here’s the first of two posts on the mentioned events and their meaning, short, sweet, and sour. I’ll sketch out the big facts and ideas; the second post, to follow in a few days, will be rich with more detail.

If you’re reading this, you probably know that the media has been raining on Texas all week, due to the near collapse of its power system. A winter storm was the primary trigger, yet the tempest of adverse attention has been unrelenting, and though rather deserved, not entirely helpful. Content-wise, much has been covered, and much has been missed.

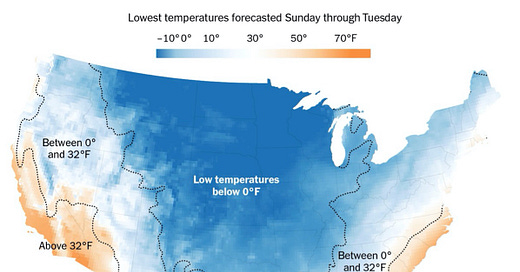

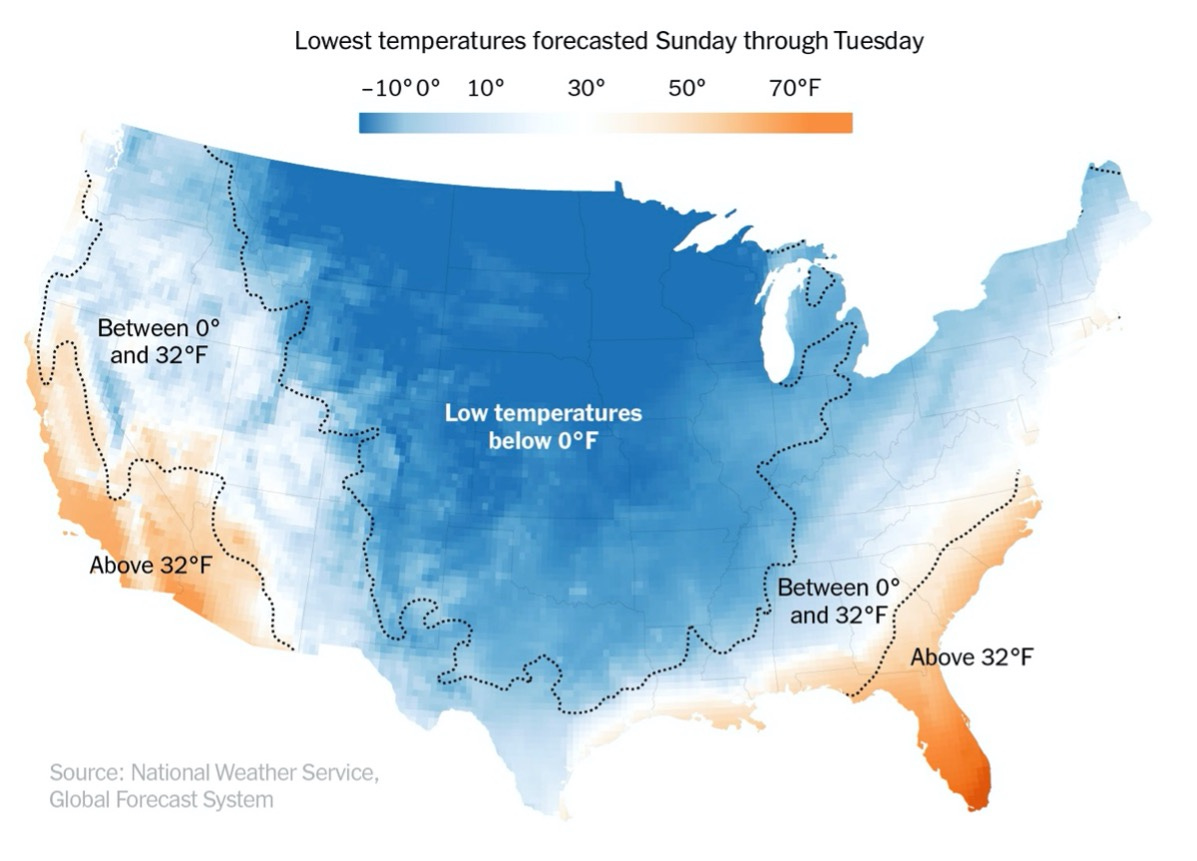

In truth, Texas was only part of a much larger circumstance involving nationwide infrastructural decay. A massive sweep of polar air moved across the continental U.S., bringing many troubles and proof of how profoundly vulnerable the world’s superpower really is. A map showing the full spread of the deep freeze is needed.

It pays to be blunt here: the fragility of our electricity system, deepened by decades of widespread neglect, now constitutes a major national security issue.

Electricity is fundamental for the existence of modern society. Somehow, we have to keep being reminded of this by storms, wildfires, cyberattacks, and more, in order to just forget it again soon afterward. The climate dimension to the problem is now prominent and immense going forward. Too many officials continue to talk about forms of severe weather as “black swan” or “freak” events. Such is simply a way of embracing ignorance and denying responsibility. The changing climate is driving such events worldwide (the technical field of relevant study is known as “extreme event attribution”), so they must be expected.

Texas now ranks among the worst state examples of suffering by negligence and bad ideas. But it has more than a few companions. America finds reason to build weapons to destroy any foreign city on any continent but struggles to keep the lights on in its own.

In brief, then, what happened when the Arctic came to town? I offer a factual summary, with a twist at the end.

Fahget about It

In a number of states across the country—notably Oregon, Mississippi, Ohio, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia—freezing rain and snow wreaked havoc. They weighed down telephone poles, power lines, and trees, causing hundreds of local outages (ice can make trees more brittle, something I saw many times working as a climber for a tree care company back in the Pleistocene age).

While ice storms routinely bring damage, they should not be creating so many power outages nationwide any longer, as the problems are well-known. The situation has worsened in the past two decades due to the lack of adequate monitoring and maintaining of the transmission side to the grid. This means not only clearing trees and other vegetation away from power lines but upgrading and replacing senile utility poles. The U.S. is one of the few advanced nations that continues to overwhelmingly rely on wooden poles (there are ~100 million of these). A main reason is that they are cheaper than using other materials (cement, steel, composites), but low cost is also due to lack of replacement. Though built to last 30-40 years, most are now 50-60, and many are over 75.

When major outages occurred in CA in 2020, the media dutifully noted deferred maintenance as a contributing cause to the ignition and severity of several major wildfires and forced blackouts throughout the state. The winter of 2021, however, proves, again, what was already known: negligence leaves the grid, and much else, vulnerable to both fire and ice.

A Different Challenge

No fewer than 15 states, from Texas and Louisiana to Minnesota and South Dakota, suffered rolling blackouts of varying length between Feb 15 and 18, with problems continuing into the weekend. In every case, these blackouts were intentional. They were the last-ditch effort of state (Texas only) and regional electricity management firms that did not have enough power to meet huge rises in demand.

Polar temperatures advanced deeply into the U.S. on Feb 8, causing millions of households to turn up their heat, most of which was either electric or powered by natural gas. Since a large amount of power plants across a number of states burn gas, demand for this fuel rose rapidly over the following days. On Feb 15, two things happened. First, demand for electricity soared beyond expected peak levels; second, the cold forced offline a major amount of supply. Taking Texas as example, the loss of power, in descending order of impact, came from natural gas, coal plants, wind turbines, and nuclear.

Natural gas was far and away the overriding problem. Producing wells and pipes had become progressively blocked and lost pressure due to formation of ice and gas hydrates (an ice-like substance) from several days of temperatures in the teens and single digits. This affected supply to powerplants directly, and it happened in several states (TX, OK, LA, CO, WY, ND). The freeze-off, as it’s called in the industry, cut gas supply considerably, and some 140 or more powerplants went offline. But that was not all. The resulting rolling blackouts also shut down wells, processing units (these separate methane from other components), and compressors that move gas in the pipelines. All in all, there was a larger loss of supply and power than had ever been experienced before.

In the end, regional organizations that control power distribution in the 15-state region (I’ll name them in the next post) faced a crisis situation. There was little choice but to impose rolling blackouts. Even though some states did not contribute very much to the overall power deficit, they were subject to outages (usually short ones) to spread out and therefore minimize the consequences to each population. Except for Texas, Oklahoma, and part of Louisiana, gas production was pretty much back to normal within two days.

Don’t Mess with Texas’ Mess

The major exception, of course, was Texas. Here, I’d wager, the grid came within a hair’s breadth of collapse. Several points require mention. Gas generates 45%-48% of the state’s power, far more than any other source. It also fills the gap when other sources are reduced for any reason. In the week after Feb 8, as the cold air settled in, the rising demand for power and heat was met with gas, until the freeze-off, and then it wasn’t. Over 4 million people went into cold and darkness and then lost water (low temps. meant cracked pipes; no electricity meant dead pumps). This number decreased to about 2.5 million after two days, but because gas exports to northern Mexico fell, outages happened there for 5 million people.

Other states could not offer much help to Texas, even if they had no such problems. Why is that? In the 1930s, Texas stood its ground against oversight by the federal government, demanding it not be connected to the national grid and remain an island of self-reliance.

Since the 1990s, moreover, the gas and electricity markets have been deregulated. Before becoming president, Governor George W. Bush put this into play, and for a while it seemed to work pretty well. But the system isn’t built to deal very well with massive losses of both gas supply and power plant availability.

The idea has been that the latter would not occur, because companies had incentives to not let this happen. During periods of ultra-high demand, prices would surge and companies would gain a windfall, which they would partly invest in upgrades to assure they could continue to function under any conditions. But deregulation meant there was never a requirement for such investment. That would have been a type of regulation, which the plan did not want. And despite the recommendations in a 2011 investigation of a freeze blackout event that year, companies never fully winterized. Operators made a different calculus and chose not to spend the money. The free-market incentive system proved unequal to the real world. What the state has reaped, in the technical jargon an industry friend offered me, is a “self-ignited clusterfuck.”

Current Governor Greg Abbott put it somewhat differently: “What happened this week to our fellow Texans is absolutely unacceptable and can never be replicated.” It even seems possible the “r” word might be whispered again in the halls of the governor’s mansion. Perhaps. But even if a sensible regulation or two is added to gain the public’s trust, it seems unlikely that state Republicans will change the system or join the rest of the nation’s grid landmass.

One point that has gone unmentioned: in the whole mess that affected the heartland and southland, but other parts of the country as well, the single source that remained most reliable by far was nuclear. The one reactor at the South Texas Plant that went down did so because of a sensor reading for a feedwater line (a legitimate reason), and it was up again in just over 48 hours, while gas, coal, and wind all remained down. Loss of the one reactor meant a quarter of nuclear power was offline, while the figure was 40% for coal, and 50% for both wind and gas. Throughout the greater region, too, nuclear plants online at the beginning of the polar invasion remained so.

Acts and Sayings of Sages

Texas’ mess had some other contributions that deserve mention. To discuss these requires that I change the style of this writing a bit. It also demands a confession: I have no abiding disfavor for the Lone Star State, none whatsoever. While there are certainly aspects of its politics, and some of its politicians, that I find less than admirable, I have spent much time in Texas, fallen in love with its magnificent landscapes and extraordinary geology, benefited from time spent with many excellent and generous people, and enjoyed wonderful moments in some of its culturally rich cities (not only San Antonio and Austin). This being said, I also recognize that there are some individuals who do not represent the state particularly well.

First, I take note of Sen. Ted Cruz from Houston. Sen. Cruz proved himself a stout defender of the grid’s Alamo moment by fleeing with his family in the midst of the crisis to a nice, warm and well-lit hotel in Cancún (in the country he argued we needed to wall off from the U.S.). Doubtless this was done not to be a good dad to his daughters, as he suggested when caught, but to provide time and space for him to clear his mind, overburdened with empathy for the poor and non-white people of Texas, and plan a heroic return to quickly repair the state to normalcy. But no. It seems more of an effort to provide reasons for outrage and material that comedians could use from sea to shining sea. Only last year, as wildfires raged in California, threatening thousands of lives, Sen Cruz righteously criticized that state for its inability to provide reliable electricity.

Texas governors have stood less than tall as well. Rick Perry bravely said that “Texans would be without electricity for longer than three days to keep the federal government out of their business.” Thus, another deeply felt comment on behalf of the state’s lower income people, arriving from a gentleman who most recently served as the federal government’s head for the Department of Energy.

Then, there were Governor Greg Abbott and U.S. Rep. Dan Crenshaw (R), who made statements claiming that renewables, esp. wind power, were the real cause of the Great 2021 Texas Grid Collapse. These comments were not just incorrect but unexpectedly, breathtakingly foolish (just being factual here). Foolish, because they were so easily and so quickly proven to be dead wrong. Unexpectedly foolish, because Republicans have been directly involved in building a new industry that has made Texas the largest generator of wind power in the country. And breathtakingly foolish, because the industry now employs 26k people and strongly enhances the state’s ideal of energy self-reliance. Nonetheless, perhaps in an attempt to offer comfort and protection to oil/gas and coal companies and workers, Gov. Abbott told Sean Hannity on Fox News, “Our wind and our solar got shut down... and that thrust Texas into this situation where it was lacking power at a statewide basis…As a result, it just shows that fossil fuels are necessary for the state of Texas…”

To clarify further, wind provides up to 20% of total annual power. But output is routinely much lower in winter, and though it did fall significantly during the deep freeze, the power lost was a fraction of that due to the curtailed supply of natural gas. I’ll share the actual data on this in my next post. It’s quite revealing. Solar, on the other hand, is a very small contributor in winter, as the data will also show.

That’s enough for now. More on this matter, with data, soon!