North Korea, under the hand of Kim Jong Un, seems an odd choice for a post on energy. His is a regime, after all, that can build nuclear weapons but can’t keep the lights on.

Readers familiar with the “Earth at night” images from NASA will have noted that after sunset, South Korea becomes an island, with Seoul like a brilliant diamond hanging from the thin bright chain of lights curving along the border. North of this border is as black as the surrounding seas.

It wasn’t always so. Disappearance of the DPRK—the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, which is not democratic, for its people, or a republic, but is Korean—counts as recent history. Prior to the Korean War, it was one of the most industrialized areas in East Asia. Korea as a whole lay under Japanese control from 1910 to 1945. Occupation proved cruel and pitiless in many ways but advantageous in one. Japan’s militarist regime launched methodical surveys showing the North had abundant metals and minerals, including coal, that Japan mostly lacked. Coal and hydropower were harnessed to power mining, factories, military bases, and also urban modernization.

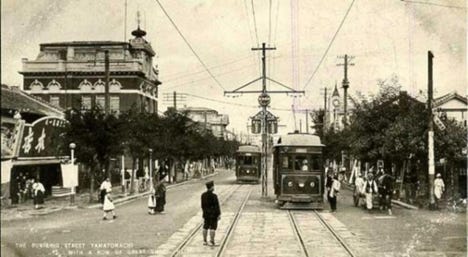

One such plant was among the largest ever built to that time. The Sup’ung Power Station on the Yalu River, the border with China, had six turbines each rated at 105 megawatts (MW), higher than any in existence. It helped the DPRK supply not only its own power, but 90% of that in the South, and some for northeast China as well. At that time, the 1930s, the ancient city of Pyongyang had electric trolleys, shopping districts, government buildings, neon signs, streetlights. If created then, NASA’s image would have been reversed—a glowing peninsula in the North with dark sea to the south.

Geologically speaking, North Korea isn’t really as well-suited to hydropower as might appear. Though its mountains receive annual snowfall and rains of the monsoon, river flows are exceedingly seasonal. They peak in July and August and then fall rapidly by late September. A number of the chief rivers, such as the Chongchon, are so low in early summer that, as American soldiers discovered, they can be forded on foot.

Virtually all of DPRK infrastructure was destroyed during the Korean War (1950-53). This was a monstrously brutal conflict in which a higher percentage of civilians were killed than in WWII, esp. in the North (~ 15% of the population). All major cities were either destroyed or severely damaged. Legend has it that that every square meter of the DPRK received either a bomb, several bullets, or both.

The country was rebuilt by the Soviets and Chinese, and by 1960, the country was again well advanced beyond the South. But this did not last. Assistance from its giant communist neighbors did provide the DPRK with markets for its manufactured goods and raw materials, as well as expertise in irrigation, fertilizers, and mechanized planting. But despite a national policy of Juche, “self-reliance,” North Korea remained deeply dependent on the Soviet Union. When this collapsed in 1991, the DPRK went into free fall without a parachute.

Collapse

A year of intense drought in 1993 was followed by massive, typhoon-related flooding between 1994 and 1996. Dams were overtopped and breached; highways and railways washed out; bridges swept away; power plants wrecked; transmission lines downed; water treatment plants taken out; topsoil lost; coal mines flooded. Blight and famine followed, with millions starving, homeless, destitute. Social order did not collapse, as people banded together for shelter and sharing. Yet communal kindness couldn’t replace failed harvests. Lack of fuel forced farmers back to premodern methods, with hand-held plows pulled by animals. Hillsides were sheared of forests for firewood.

International aid was permitted but selectively administered by a despotic regime. It rerouted food shipments to the capital and the military. Estimates on the number of deaths nationwide vary from 1-3 million (official DPRK numbers remain at around 225,000). A generation of malnourished children was a long-term result. Kim Jong Il, however, continued his fondness for expensive brandy, golf, and the myth that he invented the hamburger.

The Great Famine ended in 1998, but the country never fully recovered. Crisis from drought and flooding returned often between 2000 and 2019. Regime priorities to maintain a strong military and advance a nuclear weapons program helped ensure that the country is highly vulnerable to natural disasters. Continued proclamation by Kim Jong Un about the agricultural glories to come do not seem enough to make it happen.

The Kim dynasty has done its part to keep the DPRK a failed energy state. In truth, the country’s situation has its complexities. With Soviet help gone and China unwilling to adopt the same role, the North has been unable to rebuild a fully functioning grid system. As late as 2014, the entire country of 24 million was estimated to have 3-5 GW capacity, about equal to the power needed for a modern city of 700,000.

UN and US sanctions have added to the scarcity of fuels. The aim, to stem the North’s nuclear weapons and missile programs, has been a complete failure. As of 2019, Mr. Kim’s arsenal was estimated at 20-30 warheads, with enough plutonium for another 30-60. He could now turn to building civilian reactors to provide reliable power to his people. Yet he remains unsatisfied, now seeking one or more submarines with nuclear weapons capability. Meanwhile, his missiles can reach anywhere in NE Asia and are able to cross the Pacific.

The regime wanted to be a nuclear weapons state for 70 years. Its first leader, Kim Il Sung, asked the Soviets and Chinese to be nice and give him a few nukes or show his scientists how to build them. Both countries said no. But the Soviets built a small research reactor at Yongbyon in the 1960s and taught the North Koreans how to run it. They learned fast; within a generation, they had begun to separate plutonium from the spent fuel. The story is long and deeply disturbing (here’s a short version), with the US playing a central role. By the mid-2000s the DPRK had a stockpile of plutonium and uranium enrichment facilities; it was making its own nuclear fuel. In 2006, it tested a nuclear device, shocking the world. Five more tests between 2009 and 2017 left no doubt.

But the core point is that instead of using nuclear energy to generate electricity, the Kim Dynasty built humanity’s most terrible weapons, leaving the people to suffer and starve. Nuclear weapons, as the goal of goals, hollowed out the living country.

Solar Naissance

North Koreans, however, have not been idle when it comes to energy. The country is no “hermit kingdom.” Its people have long traded with China across the Yalu River border: appliances, cell phones, computers, tvs, food stuffs, rice cookers, batteries, water purifiers, small generators, and more. Trade, legal and otherwise, with South Korea has also been frequent.

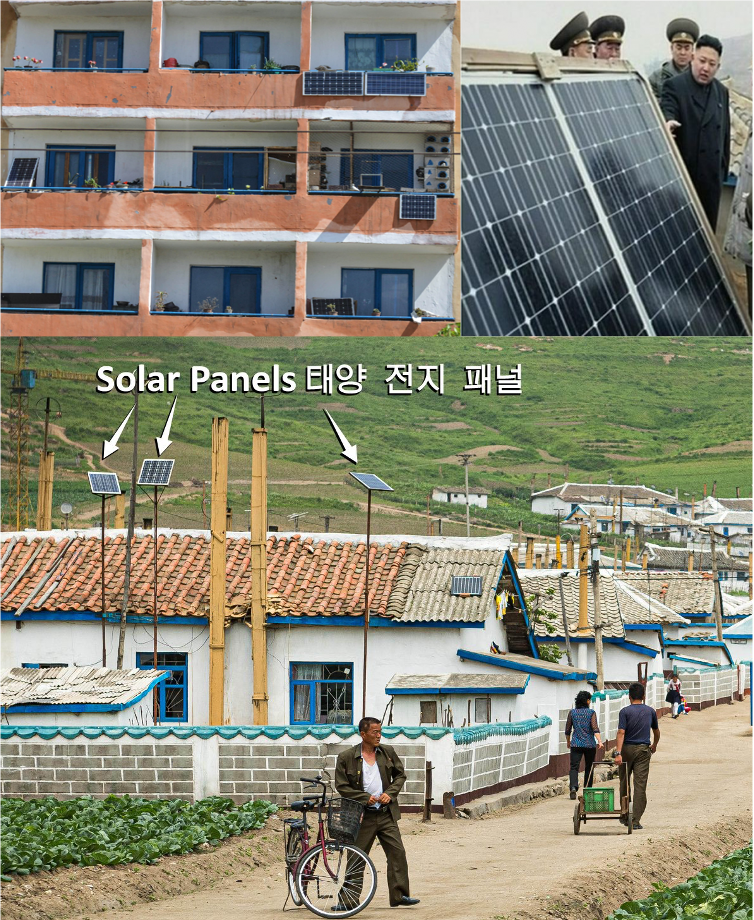

To power their homes, people couldn’t—and still can’t—rely on the broken grid. But since 2010, they have turned elsewhere, buying cheap solar panels from China. This began as a way to recharge cellphones or power a few lights. But such use rapidly grew to include multiple panels, which were also able to power teahouses, bars, game halls, and other entertainment centers. China, the world’s larger panel manufacturer, has had plenty to sell, be stolen and smuggled. Cheap has gotten cheaper. A 20-watt panel costing around $44 in 2015 can now be replaced with a 30-watt version for a mere $15. That’s quite good, since a 20-watt version can’t do much. Two 30-watt panels together with a battery can do significantly more.

By 2018, such panels were combined with batteries and diesel/gasoline generators to form microgrids in villages, towns, and parts of urban areas as well. Verboten early on, the panels are now encouraged (Juche forever!) and aren’t included on any sanctions list. But self-reliance in this case also takes the government off the hook for building back the grid. State media even brags about solar cred: schools, factories, farms, businesses, even ferries, are all powered, they say, by that magnanimous disc in the sky. Given the government’s long history of leniency toward facts, we might let this pass without comment (a ferry?).

Observers believe at least 50% of North Koreans now use solar power. From one point of view, this is astonishing. No other country approaches such a figure. As of now, the DPRK qualifies as the most solar-powered nation on Earth. Panels are everywhere, on roofs, high poles (to prevent stealing), buses, lamp posts, balconies, and the windows of apartment complexes. There are also solar hot water heaters on houses and apartments.

North Korean entrepreneurs now make their own panels. Domestic companies selling and installing them have become common. According to Kang Mi Jin, a recent defector from the North: “a 50 watt panel sells for $23, while a 100 watt panel sells for $37…Wealthy households use 250 watt solar panels…to power luxury household electronics purchased in the markets.”

At 100 watts and batteries, a family can power a laptop, ceiling fan, several lamps, a DVD player, cellphone charger, small tv (perhaps two or three of these at the same time). But recall: a common incandescent light bulb in the West demands 100 watts (these should be exchanged for 13-watt LED versions asap!). An average house in South Korea, if powered by roof panels, would install around 3,000 – 5,000 watts.

None of this means the DPRK will soon join the OECD club of wealthy nations, then. South Korea was invited in 1996, after 35 years of spectacular growth. I spent time in Seoul in 1979, and it was still a developing country—small shops; outdoor markets, poverty, no high rises or urban malls, many soldiers, and so on. Compared to Tokyo, it was a journey to an earlier era of East Asian history. Barely a generation later, the world was learning Gangnam Style. The North will not reach such levels soon, perhaps ever.

A Final Word

Nonetheless, it sounds like satire. The same country imperiling the world adopts an energy source developed to save it. Nuclear weapons and solar power aren’t natural bedfellows (one can only imagine their pillow-talk). The people, that is, have proven desperate and resourceful, the regime paranoid and self-defeating.

The DPRK is proof of two things that seem unrelated. First, nuclear weapons do not make a nation secure. They make it more fearful and divorced from its people. Second, solar power will not save North Korea from its needs. Nor will it save humanity from its immense and complex environmental legacies. Much more will be needed.

Perhaps these two “lessons” are related after all. Mr. Kim has said he intends a parallel future of warheads and prosperity, that he will favors the second once the nation is safe. But it seems unlikely ever to be safe; nuclear weapons will prevent this. And prosperity will require a modern energy system to power a functioning national economy. For now, the prospects don’t seem especially good for either of Kim Jong Un’s goals. It is, after all, in the nature of murderous dictators to bathe in the chill waters of self-delusion, no matter how cunning they believe they might be.