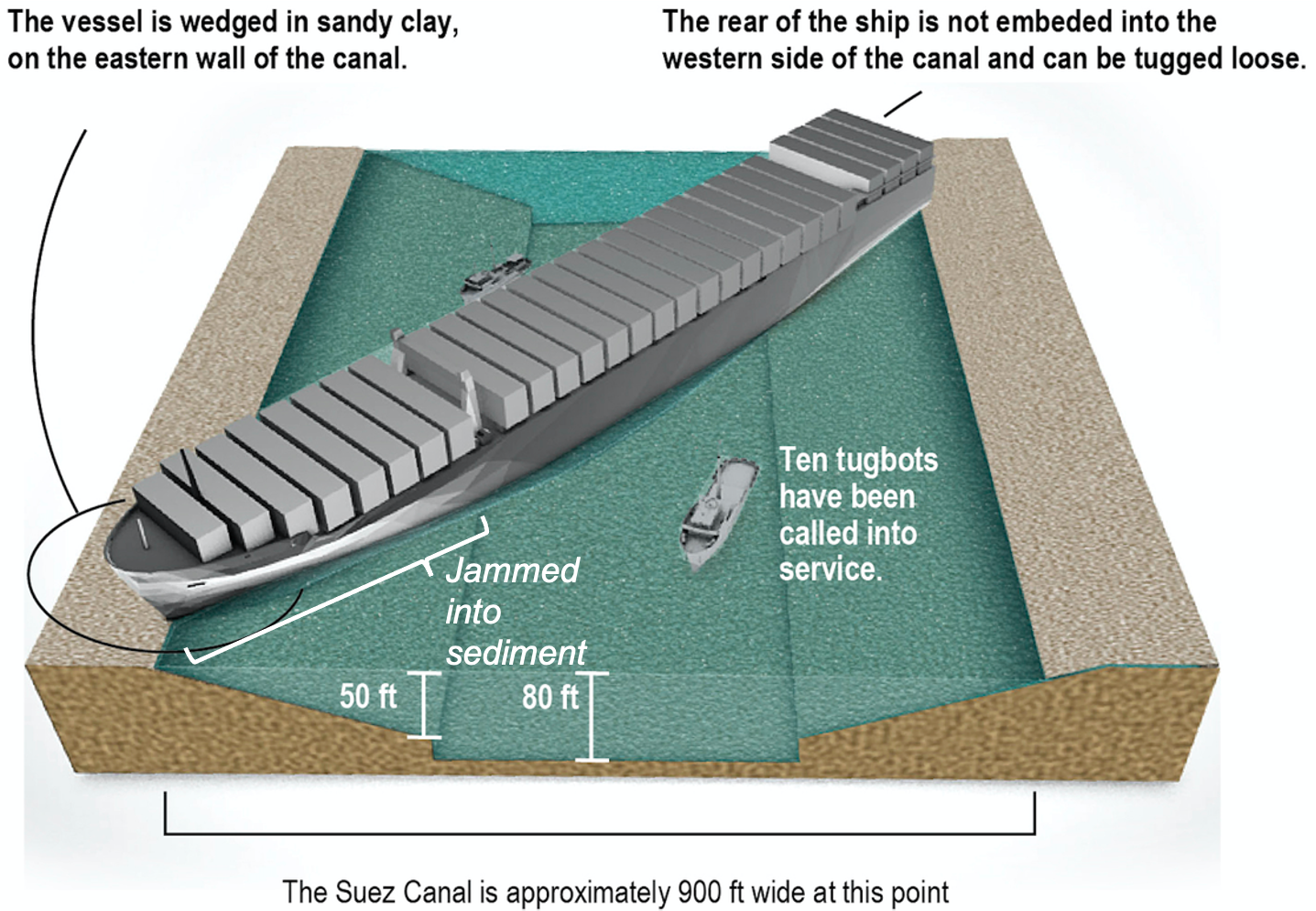

A short post about a long ship wedged in a tight space. By now, you know about the container ship, Ever Given, enroute from China to the Netherlands (Rotterdam, biggest port in Europe), that was blown off-course by high winds and jammed into the margin of the Suez Canal for an entire week, holding up part of the global economy. The ship, at 1,300 ft long and 195 ft wide (400m x 60m), is one of the largest container vessels in the world, as long as the Empire State Building is tall (to the tip).

This makes it about 445 ft (135 m) longer than the width of the canal at this site. But because it drafts to 52 ft and has a curved underside, it actually made contact with the underwater slope of the canal at about 36 ft depth (11 m). The ship is actually 716 ft longer than the navigable canal at this point.

There seems a real question about whether the ship is too big to pass through under all weather conditions. Climate change teaches that it is the more infrequent but extreme events that do the most damage. It seems fair to suggest that an event of this kind was likely to happen, whether due to winds, an engine malfunction, terrorist event, cellphone call, or other fundamental human error.

In truth, canals through history have allowed boats longer than the waterway was wide. But let’s be serious, these weren’t floating skyscrapers. They didn’t weigh 200k metric tons (220k tons), giving them enough inertia to easily penetrate more than 150 ft of a sediment wedge (see above diagram). It seems the ship was also “speeding,” at 13.5 knots (15.5 mph/25 kph), well above the 7.5 – 8.6 kts speed limit, to try and maintain position in the strong winds. All ships that go through the canal have Egyptian pilots on board, so this must have been ok’d. (Don’t ask me about the physics of speeding up in a cross wind to maintain direction. It’s late at night, and that’s a bit above my intellectual pay grade right now).

These supergiant container ships were first permitted for canal use in 2015 by the Sisi government, when an upgrade to the Suez was completed. The project, in fact, was a geopolitical as well as an economic move. It was a competitive response to widening of the Panama Canal and the larger ships allowed through there, called “Panamax” (length up to 366 m, or 1,200 ft). The Suez can now brag that theirs is just as big!

The new-and-improved Suez corridor has the ultimate goal of doubling traffic, to 97+ ships per day. This would mean a far bigger back up if another Suez jam (song title?) happened: think 800 ships instead of ~400. Meanwhile, the whole episode has been treated in the news with wonder and in social media with meme humor. The situation does have an element of absurdity.

Bits of History

Geopolitics and other troubles have long been part of the Suez Canal. When opened in 1869, the canal was less than 30 ft (9 m) deep and 200-300 ft wide (60-90 meters) at the surface. By today’s standards, no yacht of a tech billionaire or Saudi prince could manage it. But even in its first two decades, the canal saw thousands of ships run aground (yes, thousands). Over time, it has been repeatedly widened and deepened to keep up with growing ship size and traffic.

It was contracted in 1853 with the Ottoman Empire by France, under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps, a diplomat and impresario. The project was roundly hated by British imperialists, who viewed it as an attempt to break their grip on east-west trade, esp. involving India. They weren’t entirely wrong. In 1882, they invaded Egypt and took control of the canal until 1956, when Gamal Nasser nationalized it, precipitating the Suez Crisis, a major Cold War event. Israeli, British, and French forces attacked the Egyptians but were pressured to withdraw by the U.S., who threatened sanctions—including shut-off of oil exports (America used the “oil weapon” before OPEC did)—while the Soviets supplied Egypt with arms. It ended peacefully, with everyone admitting their mistakes and shaking hands (not).

When completed, the Suez was hailed as a modern marvel. Perhaps it was, since mostly dug by industrial machinery. But it began in forced labor, using over a million Egyptians with picks and shovels(!), in shifts of 20k. By comparison, the Pyramids were built by freemen, hired, trained, fed, housed, and given medical care (enslaved Jews were not involved). Though the canal was originally planned as a hand-dug project, progress was slow, and humans had an annoying tendency to be overworked, injured, and sick. Egypt’s pasha ended forced labor in 1863; machines soon arrived.

But as a “marvel” only possible in the modern era, it was not. China had completed its Grand Canal system linking the Yangtze and Yellow rivers over a distance of 1,100 miles (1,776 km) in the Sui Dynasty (6th-7th c. CE). Moreover, the ancient Egyptians themselves undertook a number of canal projects as early as the Middle Kingdom, attempting to link the Red Sea to other bodies of water.

One final, interesting fact. The French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi asked if he could erect a 90-ft statue of a woman in Egyptian garb at the entrance to the canal, titled “Egypt Bringing Light to Asia.” No, said Lesseps. The idea, however, bore fruit for Bartholdi in 1886, when the Statue of Liberty was unveiled in New York Harbor.

Fast Forward to 2021

International traffic through the canal has long revealed, in a narrow space, the ever-growing level of trade and dependence between Europe and Asia. Today, this is around 19,000 vessels a year (the southern route around Cape of Good Hope, adds ~7,000 km and a week to the journey), about 50 per day.

I could talk long and windy about how the canal seems to have repeatedly played catch up to ship size and load. Today, even bigger ships are on the way—Ultra Ultra Large Container Vessels (this is a failure of language: why not call them “Gigaships?”). It’s an old economic story of per-unit (container) cost decreasing with number shipped in each load. Is there a limit? But we live in a new era of giganticism—the Burj Kalifa (>2,000 ft tall), a global pandemic, Trumpian ego, housing prices in San Francisco.

Nearly a third of the ~430 ships held up by the Suez jam were oil and LNG (liquefied natural gas) tankers. Enough oil has been unavailable to the market to help urge a rise in prices of more than 5% in just a few days--over 6% in the U.S., to above $61. This could have a real impact, if prices like this persist. At $60, US companies active in shale and other low-permeability (need to frac) plays can make decent money (and pay off some debts). They have been waiting for this.

It is exactly what OPEC+Russia are afraid of. Within just a few months, US production could grow enough to put major downward pressure on global prices, unless OPEC+R cut their own production again. They won’t want to do this. In 2020, to push prices up from ~$35, they shut in over 8.5 million bbls/day, a huge volume, decreased slightly to 7.7 million bbls/d, when lockdowns meant people weren’t driving.

As the graph shows, it worked. Prices did climb during 2020, and not by a little. The low point in April is when the big cut took place. In June, OPEC+R reduced their cut to 7.7 million bbls/d, and prices stopped rising, but not for long. By November, many countries were opening up again, with people driving much more. Demand went up, and so did prices.

Yet, in this radical attempt to seize control of the market, OPEC+R gave themselves away in a more serious area. Yes, it told the world that the petro-states mean business. But that’s precisely the problem. None of these countries have done very much to diversify their economies away from abject over-dependence on fossil fuel exports. The >8 million bbl/d self-inflicted cut showed they are willing to take a real hit in order to preserve their fatal addiction to oil/gas revenue. Judged by their strongest actions, they are not in line to do anything significant about climate change.

You may stamp and yell about evil oil companies, but OPEC and Russia are the true suppliers. They own the oil, not Exxon or BP. National oil companies, like Saudi Aramco, are monopolies that control all the oil and gas in Saudi Arabia (or Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, etc.)—far more than all the international oil/gas firms combined. For now, the national companies of OPEC & Russia rule the world of oil supply, and that gives them real economic and political power. But it is a deep root in the soil of the past. The Energy Transition, however long it may take, will not be kind to them.

Surely, You’re Choking

The map below shows density of marine traffic averaged over 2019. White areas equal highest density zones.

The yellow arrows indicate 8 different “choke points” through which especially large amounts of shipping take place, including oil and LNG tankers—but also, in many cases, parts for wind turbines, solar panels, hydropower and biomass plants. One of these choke points, the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia, doesn’t have much traffic right now. It soon will. Climate change continues to reduce Arctic sea ice, and the Northern Trade Route between Europe, Russia, and East Asia will rise in importance, not a little. Notice that it has the potential to reduce traffic through choke points 7, 5, 4, and 2.

The numbers correspond to these geographic points: 1. Bering Strait; 2. Molucca Straits (Singapore); 3. Straits of Hormuz (Persian Gulf); 4. Bab el-Mandeb (Red Sea); 5. Suez Canal; 6. Dardanelles Strait and Bosporus; 7. Strait of Gibraltar; 8. Panama Canal.

Choke points are geographic, yes, but it is the flow of human demand and desire that renders them economic, geopolitical, and security concerns. In the 1800s, the Suez was a new stage in East-West relations, soon joined by the Panama Canal, which, though begun by the French (Lesseps again, eager for new glory), added to American power. An influential geopolitical theorist, Halford Mackinder, predicted in 1904 that the U.S. would be as linked to Asia in the future as to Europe.

WWI and WWII made Gibraltar and the Dardanelles crucial. Then, by the 1970s, with Middle East oil essential to advanced economies, the Straits of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb gained flows of security anxiety, enhanced by the Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War. They remain so today.

But now, in the 2020s, realities of global trade and a disintegrating international order, together with the rise of a more assertive China, have made all of these choke points foci of strategic worry. The Straits of Malacca bring the largest amount of marine traffic through a tight space—40% of global trade, or about 100k ships per year. Most of it heads to or from the South China Sea, which Beijing is seeking to seize in its entirety. Something of a global security concern there, you might say.

Ever Given and the Suez tribulations are a reminder for all of this. And I didn’t even get to talk about supply chains…